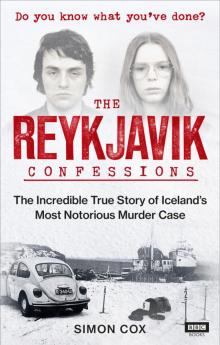

The Reykjavik Confessions Read online

Page 16

Although Einar Bollasson had been released, Schutz was still looking for evidence he was linked to Geirfinnur. He sent off a hotel guest book for handwriting analysis to see if the two men had stayed there at the same time. This proved to be another dead end.

Schutz also decided to issue a public appeal for information on four issues relating to Geirfinnur’s disappearance. First, if Geirfinnur had been in contact with any owners of small boats. Second which was a very vague request, if anyone knew whether Geirfinnur had revealed a secret that led to him being threatened. Third, if anyone knew if Geirfinnur had been paid to keep quiet about something. Finally, if anyone knew about the smuggling of alcohol that was supposed to have taken place. It was the kind of appeal you might expect a few days into an investigation, not two years in. It showed publicly there was still an awful lot that the police didn’t know.

They were also still looking for the car that took Erla, Saevar and Kristjan to Keflavik and more importantly, the driver. For months, the suspects said it had been Magnus Leopoldsson, the Klubburin manager, but he had been freed as there was nothing to connect him, so the question remained: who was the driver?

With Schutz’s arrival, the suspects were no longer being treated as one single group in Sidumuli. On 15 September Erla was transferred from Sidumuli to the old prison, the Hegningarhusid, as the detectives were worried for her safety and that she might harm herself. She would still be in solitary confinement but in a bigger, more comfortable cell. The Hegningarhusid had just one corridor, with doors separating the male section from the female. From her cell she could hear life carrying on outside the prison; people walking on the street, joking and hurrying down Skolavordustigur towards the shops and coffee bars where, over a drink, they might speculate about the ‘killers’ being held in prison. Her detention had been extended for another 90 days.

Tryggvi was also agitating for a move out of Sidumuli as he was often left for weeks with no investigators talking to him. The restrictions on Tryggvi had eased slightly; he was given a brief chance to stretch his legs for 15 minutes a day in the exercise yard, albeit alone. Orn Hoskuldsson had granted the inmates this small concession. There wasn’t much to see in the yard but Tryggvi could feel the rays of the sun, the chafing wind. It gave him a sense that he was still part of this island that viewed him and the other suspects with suspicion and fear, fuelled by the regular sensationalist press coverage that took the police at their word and reported every little snippet of gossip.

He would still have occasional interviews about the Gudmundur case. There were two of these in September but there was little new he could tell the detectives. He still didn’t remember what had been done to the body, its transportation to the lava or its final resting place. The answer would have to come from elsewhere.

Over the summer, Schutz had ordered extensive psychological assessments of the suspects. Tryggvi had gone through two months of this in June and July with the psychiatrist Asgeir Karlsson. His report set out Tryggvi’s chaotic young life drinking and taking drugs and how he had been hospitalised because of his drugs intake three times. Karlsson said it was difficult ‘to get on with an accurate overview of his life because of how insecure he is and inaccurate, and he often needs to think a lot about his answers and to correct them… His judgment is poor and he has little attachment and shallow emotions, and he has some anxiety and a sense of worthlessness.’

The psychologist Gylfi Asmundsson was equally damning, concluding, ‘Tryggvi Runar is neither retarded nor psychotic but is poorly diagnosed and has character defects, which occur as (psychopathy). He has been an alcoholic from the age of 16 and dependent on psychotropic drugs (drug dependence) from the age of 17.’

Tryggvi was moved to Litla Hraun – the newer jail out on the southern coast. The move from Sidumuli considerably improved his mental and physical health. He wrote to the detective Sigurbjorn who had questioned him the most. Starved of any other contact, Tryggvi felt he had struck up a bond with Sigurbjorn in their interviews just as Erla had done. It seemed like a kind of Stockholm Syndrome, where people held captive develop feeling of trust or affection towards their jailers. Tryggvi described to his ‘friend’ how the new jail was like a paradise compared to Sidumuli. He was in good shape physically and wrote, ‘I was ready to talk to you, my dear friend. I was very grateful for what you have done for me.’ He sent Sigurbjorn good wishes for his summer holidays and hoped to hear back from the detective: ‘I’ll write more next time so hope I get a little line from you because you were my friend. Best wishes from me, Tryggvi.’

Saevar had also been having regular psychiatric evaluations with Ingvar Kristjansson, who visited him half a dozen times. In September Ingvar published a long evaluation of Saevar’s mental health. It set out his fractured, difficult upbringing with his parents splitting when he was 12 years old and him being sent away to Breidavik boarding school for ‘delinquents’. He had developed anxiety and heart problems when he was 16. The psychiatrist set out his descent into serious criminality:

In 1972 there was a major change in Saevar’s life when he acquired a new social circle of people who were older than him. In this company he has learned more about drugs and so he began to conduct drug trafficking and importation, hashish and LSD, in collaboration with others that will bring the money into this business. In total, he has gone on four trips abroad from autumn 1973 to January 1974 to buy drugs. Saevar will have described himself as a sensitive man with a love for animals and humans and has an aversion to violence.

They discussed the cases and Saevar told the psychiatrist about the conduct of the police and how he had been coerced to sign confessions, but these claims were casually dismissed by the final report.

This wasn’t the first time his mental health had been assessed. The report referred to a separate analysis that a psychologist had conducted in the spring:

Saevar constantly tried to ‘manipulate’ the psychologist and tried to avoid taking psychological tests by various means… His behaviour and reactions have all been typical of a psychopathic personality with an extremely flat emotional response… IQ 84, but the probability was that he was intelligent by nature. Profound disturbances have occurred in his personality, which were reflected among other things in shallow emotions, and disregard for antisocial behaviour.

The expert conclusion from the psychiatrist was that Saevar had no evidence of any major mental illness such as psychosis but he probably had a personality disorder: ‘He seemed moderately intelligent, his orientation, concentration and memory all seemed normal. The investigation concluded that Saevar was neither an idiot nor insane.’

These assessments were incendiary and highly damaging for Saevar. Here was expert testimony which painted him as a manipulative psychopath, with no attention paid to his complaints of his treatment at the hands of the police.

These assessments were fed to the investigators, strengthening their conviction that Saevar was a deceitful monster who couldn’t be trusted. It also justified his cruel treatment and enforced solitary confinement. For months this had been tolerated as a necessary evil, but for the first time during the investigation, questions began to be asked publicly about the isolation the suspects were subject to.

The most forceful voice was Kristjan’s lawyer, Paul Arnor Palsson, who had become increasingly concerned about the effect solitary confinement was having on his client’s mental state. Kristjan didn’t hide the difficulties he was having mining his memories and, after years of drink and drugs, having to go cold turkey in prison. At the end of August, Palsson had had enough and wrote to the court to express his grievance. This was out of the ordinary, defence lawyers rarely kicked up a fuss. Sometimes they could go through a whole trial without saying anything to defend their client.

Palsson was not in this camp of passive lawyers. He accepted that the investigation into the disappearance of Gudmundur was difficult and there was the separate but overlapping investigation into Geirfinnur. He never described them as

killings. Without a body or forensics to prove anything, to him they were still missing men. He pointed out that Kristjan had been a helpful witness, reporting everything he knew about the disappearances, but after eight months in solitary confinement he could see no reason to keep him in isolation any more. Kristjan was a hollowed out shell of his former self, racked with uncertainty, constantly changing his story to try to please the detectives. Palsson wanted him taken out of solitary confinement immediately.

Palsson’s letter to the court revealed the disdain which the police showed to the lawyers. He had been denied access to his client despite urgent requests to see him, and had been kept in the dark about any details of the investigation. The first time he’d heard about the Geirfinnur investigation was from reading press reports, and he’d only discovered Kristjan was accused of involvement in his murder in April, months into the enquiry. Orn Hoskuldsson’s team told him that he didn’t need to be present when Kristjan was questioned as he was being treated as a witness rather than a suspect. Yet Kristjan was up to his neck in it, a prime suspect in both cases, and for months Palsson had heard nothing and been given no copies of any interrogation testimony. He asked for all the files on his client and that the court make sure he was present at all future interrogations that Kristjan had.

His intervention provoked a pointed response from the detectives. A day after it was delivered to the court Kristjan was interrogated in his cell for several hours. The detectives said this was at his request; he was clearly dying to get something vital off his chest. Palsson wasn’t present and neither was he days later when Schutz and other detectives interrogated Kristjan all day. As to his other request, there was no question of Kristjan being taken out of solitary confinement. The detectives wanted to keep up the mental pressure on him to squeeze him until he had given them exactly what they wanted.

The investigation had clearly become like one of the tankers that ploughed through the Atlantic for a destination that was always just over the horizon. When fog began to form clouding their view, the captain told the crew to carry on, it would soon dissipate. But each day land looked as far away as ever.

Palsson was not the only one to challenge the treatment of the suspects. The prison chaplain, Father Jon Bjarman remained the one outsider who had visited Kristjan and the other suspects during their detention. The priest had lost count of the number of times he had walked up the gentle slope on Sidumuli Street and waited outside the wooden door to be allowed in to see the suspects. He had seen all of them on numerous occasions, and was the only person who wasn’t feeding information back to the police. He had spent many hours listening to the hardships that Saevar and the others had to endure. Bjarman was not a troublemaker, he was unfailingly polite, but he too felt he could no longer hold his tongue.

Bjarman visited all of the prisons; not only Sidmuldi but Hegningarhusid, the dark and squat century old jail in the centre of Reykjavik, and Litla Hraun, the more modern jail in Eyrarbakki, a fishing village of a few hundred people. On his visits to these jails, Bjarman had been told by several prisoners of brutal punishments including one akin to a medieval rack where they would be chained to the floor.fn1

He had spoken to two inmates with very different offences who had been subjected to this same punishment. One of them had been kept in this position for four hours. In September he wrote to the Ministry of Justice about the practice. He said there had been a shift in the culture within the jail, and there had existed an ‘abnormal state in Sidumuli since 23 Decemeber 1975’, when Saevar and his friends were arrested. Since then, he said, ‘the prisoners have been kept in constant fear’. Bjarman urged the authorities to launch an independent inquiry into the undue pressure and hardship placed on the inmates.

Such protestations from a priest and from Kristjan’s lawyer, Paul Palsson, hinted at a pattern of behaviour which the Ministry of Justice couldn’t easily ignore. They made a half-hearted attempt to investigate, questioning the prison guards and the police, who denied the claims. Their word was believed and the matter went away. The prison journals which logged all of the interrogations and punishments meted out to the suspects were never examined. The prisoners would remain in isolation for as long as the detectives wanted.

Bjarman’s complaints riled Orn Hoskuldsson, who didn’t like his attitude, and after this would intermittently restrict his access to the prisoners. In the paranoia now engulfing the detectives, they thought Bjarman, a sober Lutheran minister, was a conduit for the prisoners passing messages to the outside.

14

October 1976

The Fossvogskirkjugardur was where the dead lived. According to Icelandic folklore, they were guarded by Gunnar Hinriksson, the first person to be buried there in the 1930s. Within the cemetery’s gravel paths were simple white crosses, proud headstones, obelisks and bigger plots protected by low white painted walls surrounded by trees, their bark covered in green lichen. On one side, laid out in neat rows, were the simple stone graves of two hundred soldiers – British, American and Canadian – who had died in the Second World War. A cross and the insignia of the Royal Air Force was carved into the grey stone and in the soil, colourful plants grew, bringing new life. Set away from the road, Fossvogskirkjugardur was an oasis of calm. On some days you could even hear the gentle lapping of the water in nearby Fossvogur cove. The only interruption was the occasional hum of one of the small planes landing at Reykjavik airport bringing passengers from elsewhere in Iceland and Greenland.

One morning in October, the police arrived here with a digger, disturbing the otherwise tranquil setting. The foreman at the cemetery confronted the police and asked what the commotion was about. They told him they were looking for a body. He quipped that they had come to the right place as there were bodies everywhere, but they wouldn’t be digging anywhere. He told them to let the dead rest in peace and sent them away. The cemetery had become the focus for an increasingly desperate search for Gudmundur’s body. The police had been directed there after a bizarre set of interviews with Saevar and Albert.

During a late-night interview on 4 October, Saevar told the police about a drunken conversation he had with Kristjan in August 1974 that would once again shift the focus of the investigation:

We went to Albert Klahn and told him of our business and asked him to drive us out of Hafnarfjordur to the lava and try to find a place where we had left the body of Gudmundur Einarsson. I want to point out that we took two big black plastic bags. We went in a Toyota car, which belonged to Albert Klahn’s father. It’s yellow but I don’t remember the registration number. When we got to the lava near Hafnarfjordur, we drove for a while to try to find the place where we had buried Gudmundur’s body. After some searching we found the place, close to the red gravel pits. It was not possible to detect that the remains had been disturbed. We took two bags and put the remains in them, then took them to the vehicle and placed them in the boot. We drove to Reykjavik and went straight home to Kristjan Vidar’s at Grettisgata 82. I believe that was between 1900 and 2000 that this happened.

We stayed at Kristjan Vidar’s until 2400 or 0100. We drove off, that is to say, me, Kristjan Vidar and Albert Klahn. We took two shovels, which were in the basement of Grettisgata 82. We drove Hafnarfjadveg past the Oskjuhlid [a hill in the centre of Reykjavik] to the gate which is below the actual Fossvogur Chapel west of Hafnarfjarðarvegar. We drove the car to the back gate, and we got out here.

Albert Klahn and Kristjan Vidar had the bag together. We walked in the direction of the Chapel itself, to the north. We turned west by a narrow street, then to the south, and then I remember, we passed by a light, the lamppost in the park. Then we turned west again, and then I remember that I saw many concrete crosses at the burial site, which was for French sailors who had perished here in Iceland 40 years ago. The cemetery has a lot of paths, both wide and narrow… and I remember, we were not far from these many concrete crosses, when we found a place, we thought suitable to bury the body… it was facing in the direction of

Kopavogur [a suburb of Reykjavik]. I believe that we had dug about 60 to 70cm into the ground and then put the bag into the hole and shoveled over the earth. I remember we used shovels and our feet to smooth it over… we took the shovels back into the car and then drove to Kristjan’s home and put the shovels down in the cellar. Albert Klahn spent some time with us and I was with Kristjan Vidar all night. I want to mention that about a month later I went back to Fossvogskirkju cemetery with Kristjan Vidar and his grandmother (who was visiting a grave). Me and Kristjan Vidar looked for the place where we had put Gudmundur Einarsson’s remains, but we failed to find it.’

After Saevar told them this tale, the police asked the cemetery foreman to check the area he had described, but he came back with nothing.

Even before this latest twist from Saevar, Albert Klahn’s name had started to feature more in Saevar’s testimony, so in early October the police had brought him in for another round of intensive questioning. When he was interviewed on 4 October, Albert was sure Gudmundur’s body was in the lava. The next day when he was interrogated for more than four hours, he changed his story, he was now certain the body was in Alftanes on the outskirts of Reykjavik. The police brought him there to the beach, but when they could find no sign of a body Albert recanted and said he was wrong about Alftanes and his recollections were very unclear. This should have been a signal for the detectives to hold off, but they had to close the Gudmundur case. As Karl Schutz liked to remind them, ‘the clock is ticking’. But Albert had no idea what he was saying or doing and his inability to find the body was making him increasingly anxious. The detectives were worried about his state of mind and Orn Hoskuldsson decided to detain him in Sidumuli on a suicide watch.

The Reykjavik Confessions

The Reykjavik Confessions