The Reykjavik Confessions Read online

Page 2

Gudmundur’s body was never found; the most likely assumption was that he had been swallowed beneath the lava, forever in the long shadows, where the Huldufolk dwell, the mythical hidden elves of Icelandic folklore.

Erla Bolladottir would never forget the events of that long January night. She had reluctantly agreed to go into Reykjavik with her friend Hulda, to the throbbing excess of Klubburin, Iceland’s prime nightspot. She had been spending a lot of time by herself lately and feeling very depressed, and hadn’t felt up to socialising. Plus it wasn’t really Erla’s scene – way too straight, more disco than the hippy vibe she liked. At least there were three floors in the club, so when the pulsing beats became too much she could head up the spiral staircase to the banging rock floor at the top. There wasn’t much choice; there were only a handful of nightclubs to cater for the young who were increasingly keen to kick back against the Lutheran shackles of their parents’ generation. Erla drank a little but wasn’t in the mood to party and succumb to the sweet, mellow aroma of hash wafting through the club. By the time she left, she had missed the last bus but managed to hitch a lift back to her apartment in Hafnarfjordur with some boys she knew.

As she walked up to her apartment at number 11 Hamarsbraut, Erla was enveloped by the thick, dark folds of night. It was still hours before the thinning of the darkness, signalling morning during this beginning of winter. The tiny apartment was pitch black. As her boyfriend, Saevar, had the only key Erla had to get in by crawling through the basement window of the laundry room. Exhausted she crashed out in bed.

Later she woke, hearing something outside her window. It took her a moment to figure out that it was men’s voices, whispering in low, hushed tones. They sounded menacing and conspiratorial and Erla was alone in the apartment. Saevar was nowhere to be seen.

As she listened, not daring to breathe, she could hear that the men were checking whether she was awake or asleep. The apartment was so small that if these men could have reached in through the window they could almost touch Erla who was frozen with fear on her bed. She heard the group walk around to the front of the apartment, their footsteps cushioned by the generous carpet of snow that covered the town. The men seemed intent on getting inside, but why did they want to come into her home in the dead of night, when she was alone and vulnerable?

She recognised their voices, they were friends of Saevar’s: Kristjan, Tryggvi and Albert. Saevar had warned her that he didn’t want Erla ever to be alone with them. Albert was laid back and harmless but Tryggvi and Kristjan could turn nasty when they were drunk. They were part of the petty crime scene in Reykjavik, making money from doing whatever manual jobs they could, so that they could buy booze or hash. They had appeared at the apartment a week before. Erla remembered, ‘I was watching The Late Late Show and I turned and saw the three of them standing in the hall and I thought, “Why are they inside?”’ Saevar had been annoyed; he didn’t want them there, as, Erla said, ‘If they got drunk they could make trouble.’

Here they were, back again and she knew that she didn’t want them in her home.

Then she woke up, hot and confused, her hair slick with sweat. It was still dark and she sat up to listen to see if the men were still outside. There was no sound, just the numbing silence of winter. She realised it must have been a dream, purging her troubled thoughts of the day.

She felt marooned in Hafnarfjordur, hemmed in by the lava fields of the Reykjanes peninsula. She could guess where Saevar was, probably with another woman. He had cheated on her in the past and she was sure he was up to it again.

Last winter had been a rough time for her. Her Dad, Bolli, had suffered a stroke and was in rehabilitation in hospital. Much of the time she was alone in her little apartment. During the day she worked at the Icelandic Post and Telephone company and she would return home for interminable evenings with coal black star-filled skies.

She looked at the packet of Viceroy cigarettes next to her bed. She only had to reach across and light a cigarette and, as the smoke filled her lungs, it would calm her down. But she couldn’t rouse herself, she thought, ‘What difference does it make whether I smoke a cigarette or not?’ A cigarette couldn’t alter her miserable life. She would have to move though as she needed the toilet. It was hardly far, but she just didn’t have the energy to do it. She could feel her bowels loosening, she knew she had to leave the bed but she had no will for this most basic human task. The bed would become her toilet. How had she ended up living like this, in a tiny flat with Saevar, her boyfriend who cheated on her, was never here and yet tried to control her life?

As the Douglas DC-8 banked, climbing through the clouds, away from Keflavik airport out across the swirling grey Atlantic, Erla sat back in her seat, excited. She was on a Loftleider flight, Iceland’s self-proclaimed ‘hippy airline’, cheap, cheerful and taking her away from the, murky, bleak Icelandic winter for the crisp, winter skies of New York state. For the 18-year-old Erla, America offered freedom; a chance to escape from the conservative constraints of Iceland and enjoy the freewheeling counter-culture vibe.

It was December 1973, and Erla would have almost a month away in the country where she had spent the first seven years of her life. There was just one problem and he was sitting in the seat next to her: Saevar Cieselski. Erla was not a fan of the slight, cocky young man with his straight black hair and the dark complexion that made him stand out among the Icelandic Celts. She said later, ‘He always had an air about him that he knew everything.’ She had seen him around town when he would flash his winning smile. He had boasted that he knew about Erla and her family; so much so that she wondered if he was stalking her. The answer was far more straightforward. With a population then of just over 200,000, there are often only a few degrees of separation between people in Iceland. That was the case with Erla and Saevar, who had first met many years before.

Erla’s brother Arthur had spent summers working at a farm owned by Saevar’s grandparents. Arthur shared a room with the young Saevar and liked his manner. Erla remembered the sweet ten-year-old Saevar who didn’t say much to Erla and her sisters when they visited the farm, but smiled a lot and took them to the barn where he showed them how to jump into the hay.

The sweet boy had grown into a troublesome teenager with a reputation for pilfering and petty drug dealing. He was sleeping with Erla’s good friend, Hulda, and she was bemused: ‘I couldn’t understand her choice, I really didn’t like him.’ Erla was supposed to be making the trip to the United States with Hulda but when she pulled out at the last minute, Saevar took her place.

At least they wouldn’t have to spend long together as the plan was for them to part as soon as they reached JFK airport in New York. Saevar was heading to his family in Massachusetts to sort out an inheritance from his estranged father, Michael, who had been killed in a car crash. Saevar had a complicated relationship with his father who’d believed in the old school parenting of ‘my way or the belt’. And yet his death was a massive blow to Saevar who was adrift with no strong role model to draw him back.

As they chatted on the flight, cocooned alone above the clouds, miles above the real world, Saevar started to work his magic on her, persuading Erla to let him come and stay with her in Buffalo, New York where she was staying with friends.

Buffalo was a city dominated by steel and grain mills, the General Motors car factory and the football stadium where tens of thousands of people would gather in freezing conditions to watch the Buffalo Bills and their star running back OJ Simpson. To Erla, it was beautiful; a welcome respite from Iceland. She had a strong affection for America from her time there as a child when her dad worked as a manager for Icelandair at JFK and the family lived in Long Island. She had fond memories of days at the beach playing with her siblings.

Erla had missed the sprawling American suburbs with their wide, tree-lined streets, full of detached houses with clipped lawns and expansive back gardens. Saevar was not the ideal house guest, though; he had nightmares and would wake, shouting

in his sleep. These were the dreams he never discussed with anyone, remnants from a dark chapter in his childhood. This disturbed Erla’s friends and after a few days she decided his behaviour was too much to take. She dispatched her awkward travelling companion to his relatives in Massachusetts while she stayed on in Buffalo, soaking up opportunities she would never get in her provincial hometown.

Buffalo was on the touring circuit so the city’s football stadium would often shake with a different roar, as mega bands like Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd played there. There was also the chance to hang out with musicians, who Erla would never get to see in Iceland, like famous jazz pianist, Chick Corea, who she chatted to at a friend’s college gig.

There was more fun to be had in Washington DC where she stayed with her friend, Steve, whose father was a professor in Icelandic literature. Steve had a mane of black curly hair and a penchant for high leather boots. Saevar had soon tired of his family in Massachusetts, though, and he called Erla every day until she agreed to let him stay with her. It was an early indication of his persistence and growing obsession with Erla.

The three of them would hang out at Georgetown University, lying on the grass smoking joints and planning how to change the world. Saevar never joined in with the smoking or drinking. He had started indulging at a young age; he was 9 years old when he gave up drinking, 16 when he stopped taking hard drugs like LSD – the drug of choice in Iceland at this time, along with cannabis. For Erla, though, this was the life; she could happily stay here forever. She had hitch-hiked from Providence to Maine that summer and was already planning her next trip. America held endless possibilities.

When Steve threw a leaving party for Erla, it seemed like the whole neighbourhood turned up. It was the biggest party she had ever been to, there were people everywhere and the booze was flowing. Erla stuck to Coca-Cola, but after a while and a long, particularly dull chat with a Vietnam vet, she began to feel trippy, in a way she hadn’t experienced before and didn’t like. She had tried LSD and thought she might be having a flashback.

She needed to be alone, somewhere quiet. She made her way upstairs looking for a place to lie down and get herself together. She stumbled into an empty bedroom, pitch black except for a tiny red light in the corner. Fumbling her way towards the light, she tripped over Saevar. He was in a mess too, and suspected someone had slipped LSD into his drink. They lay down side by side, listening to Frank Zappa and Pink Floyd and talked for most of the night. ‘We opened our hearts about everything,’ Erla remembered, ‘it was the most we ever talked, he told me everything.’

There was a lot to tell about Saevar’s first 18 years. He had grown up in the east of Reykjavik, in one of the capital’s poorer neighbourhoods. His dad, Michael, was an American who worked at the air base at Keflavik as a meteorologist. He had fallen for Sigurbjorg, a beautiful blonde Icelandic girl who was the opposite of the swarthy Polish-American.

The couple moved to America but it was short lived and they returned to Iceland several years later where Saevar was born. His sister, Anna, remembers a fun-loving, happy child who loved playing with his siblings and friends. As theirs was the only house on their street with a television there was a constant throng of children who would come to the Cieselskis’ house to watch the TV and Saevar’s father, Michael, would make popcorn and brownies. The Cieselski children would create home-made theatres and put on elaborate shows for their friends with costumes and magic tricks. But behind this happy front, there was a darkness. Saevar’s father believed in firm punishment, that the best way to instil discipline was to use his belt, and he handed out this treatment to Saevar on a regular basis. It was a well-known secret among his friends who grew up alongside him in the narrow warren of streets and anodyne apartment blocks.

Away from the US base at Keflavik foreigners were a rarity – strange beings from other more exotic or scary worlds. Saevar’s surname, Cieselski, a mixture of Jewish and Polish, stood out in the ethnically homogeneous Iceland of the 1960s. Combined with his short stature and slight build it made Saevar an easy target for bullies at school. He began to truant, and then found a protector – a big, beefy kid named Kristjan Vidar Vidarsson. This worried his older sister, Anna, who thought his friends were ‘very intimidating and had a bad reputation among the other students’. Saevar also befriended Albert Klahn Skaftason, who was small, quiet and well-liked because he didn’t cause trouble. The network of streets in east Reykjavik, crammed with pebble-dashed apartment blocks and houses clad in corrugated iron to protect from the never-ending wind, became their playground.

Sigurdor Stefansson, who grew up in the same neighbourhood and would later become a close friend of Saevar, said, ‘There were very many young guys like them in that neighbourhood who were sort of alley cats – stealing from shops and so on.’

Michael had never truly settled in Iceland. After leaving the airbase at Keflavik he worked as an accountant at a supermarket but he couldn’t speak Icelandic so remained an outsider. His drinking and temper got worse and, unable to cope any longer, Sigurbjorg decided they should split. With Saevar increasingly out of control, she turned to social services for help. Aged just 14, Saevar was sent away to Breidavik, a boarding school for ‘troubled youngsters’.

Breidavik was out in the Westfjords, 300 miles and a day’s drive from the capital. It was a sprawling residential school and farm, set in total isolation 28 miles from the nearest town. When the winter weather closed in it was totally cut off. The only company was the migrating birds who flocked to the dramatic Latrabjarg cliffs and the stunning beach with soft golden sand. The school’s remoteness was a deliberate attempt to return its students to a simpler, rural lifestyle, intended to end their offending behaviour.

Breidavik had been opened by the government in the 1950s under pressure from people in Reykjavik to do something about the surge in anti-social behaviour amoung young boys who were under the age of 15 and so couldn’t be prosecuted. The school was run as a family unit with a housemaster, cook and teacher to look after the seven or so boys who lived there. In the summer, the children helped on the farm, looking after the sheep and cows and preparing hay bales for the winter. The troubled young boys were expected to stay there for up to two years to curb their problem behaviour. It was seen as a huge success story with many boys sent there supposedly cured of their delinquency. When Saevar returned from Breidavik his family were pleased with his academic progress, as his school work had significantly improved.

Breidavik, however, had a dark secret: it was a brutal and horrific place where boys were sexually and physically abused by the staff and other pupils, far away from any prying eyes of family and friends. It would be many years and many scarred lives before this horrific abuse was exposed. Saevar never revealed the indignity and humiliation meted out by the sadistic teachers and older pupils to his family or friends.

Now, years later, Saevar was lying on the floor of a bedroom in America with Erla next to him and something felt different. In his altered, vulnerable state, Saevar opened up to Erla about the gruesome years he spent at Breidavik. It was during his time there that his brutal yet still beloved father was killed in a car crash. His pain and hurt was compounded when Saevar wasn’t allowed to attend the funeral. Erla would never tell anyone exactly what Saevar revealed to her in that room (‘He would turn in his grave’), but it’s clear he was violently abused by the staff and older boys. As the bright moon melted into a watery sun, Erla began to warm to the difficult, vulnerable young man. They had ‘bonded to the point I could never leave him after that, no matter how hard I tried’.

Saevar and Erla returned to Keflavik airport in time for Christmas 1973. It wasn’t like other airports; it was a huge US naval airbase where fighter planes would be lined up in the hangars waiting to fly off to guard the Atlantic from Soviet warplanes. In the arrivals lounge, Erla’s relatives were waiting to welcome her sister who was visiting from her home in Hawaii.

Erla and Saevar had a less pleasant reception part

y, lead by the pugnacious head of customs, Kristjan Petursson. A thick-set former policeman built like a rugby player, Petursson was fixated with Saevar. He had been looking for an opportunity to collar the cocksure young man who he was certain was a key figure in the local drugs trade. Petursson believed drugs were swamping Iceland and had successfully lobbied the government to set up a special drugs court. Petursson’s obsession wasn’t shared by the small detective force in Reykjavik, though. Arnprudur Karlsdottir, a no-nonsense, chain smoking detective – and one of the first women to enter this macho world – thought Petursson was on a wild goose chase, and that he had ‘an agenda to find drugs everywhere. It was very strange to me and we would talk a lot about it, why is he always after Saevar?’ Petursson seemed convinced if he could get Saevar he would punch a hole in the growing market for cannabis and LSD. He would also make a name for himself.

At the airport, Petursson made sure Erla and Saevar faced the indignity of being strip searched, but while Erla was released, Saevar was taken away for further questioning. Back home, Erla called everywhere trying to find Saevar but he had been swallowed up by the criminal justice system. A week later she was at a party with friends when Saevar showed up. He took hold of her hand and said, ‘Let’s get out of here.’ They went straight to her apartment and Saevar told her about his week in custody.

Petursson had accused Saevar of having a kilo of morphine stashed away somewhere in Reykjavik. He had been placed in solitary confinement in the basic facilities of Sidumuli prison. This was common practice in Iceland at the time, a way of making suspects more amenable during the interrogation. Saevar maintained his innocence, but this only served to further antagonise the customs chief and Saevar was knocked about a bit, to soften him up. After a week of getting nowhere, Saevar had been released. Although free from custody he was a marked man. The police were biding their time, waiting for the opportunity to catch him and take him off the streets for a long, long time.

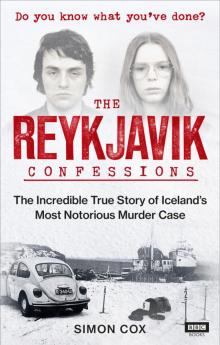

The Reykjavik Confessions

The Reykjavik Confessions