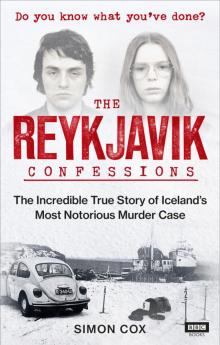

The Reykjavik Confessions Read online

Page 7

Several days later, Saevar heard about a man who was supposed to have disappeared in Hafnarfjordur on the night he was describing. Saevar didn’t have the nerve to tell anybody about that night, because he was scared what Kristjan and Tryggvi might do to him.

In Saevar’s updated account he was now the observer, scared of retribution from his violent friends. But his statement didn’t make sense. Kristjan had always been seen as his sidekick and very much in Saevar’s shadow. It seemed improbable that he was the driving force. The police were not having the same success getting Tryggvi to open up and confess. He had been questioned for over 22 hours since he had been arrested and had stuck to his story, that he knew nothing. Then on 9 January 1976, he finally cracked.

It was morning and Sigurbjorn Eggertsson was trying again to get Tryggvi to come clean about his involvement. Alone in his cell with only his ragged thoughts for company, Tryggvi told the detectives he had ‘thought a lot about this issue’ and now he was ready to explain what really happened. Indeed, Tryggvi had thought of little else in the time he had spent in solitary confinement. He had replayed the events of that night again and again as he lay on his bed, paced the cell or sat on the stool bolted to the floor:

Tryggvi was in the apartment with Saevar, Kristjan Vidar and an unknown man, who Kristjan seemed to know. This was Gudmundur Einarsson. He couldn’t remember where the apartment was or who it belonged to, but he could recall some of the layout and that there was a storage room. An argument had started between Gudmundur and Kristjan. They were shouting at first and then it ended up in a fight. Saevar came to help and when he was hit Tryggvi joined in too. Gudmundur fell to the floor but he wasn’t knocked out. He tried to get up but was swaying and was hit again. This time he didn’t get up. To make sure, Saevar kicked him in the head while he was down. It was a swift and brutal attack, over in seconds. He didn’t look like he had any major injuries, just some blood in his mouth. He remembered that Saevar had checked and said the man was dead. Tryggvi tried Gudmundur’s pulse and found no signs of life.

These petty criminals had crossed a line, moving into darker territory, but the police accounts of these confessions contain no sense of the shock, remorse or panic. In Tryggvi’s account there is a brief mention of panic as they realised they had a dead man on their hands, but it was a fleeting reference. Tryggvi said they knew they had to get rid of the dead man, but he could not remember how they carried him out.

Tryggvi was the last of the suspects to fall. Days earlier Kristjan had given detectives a vivid account that seemed to tally with the others’ statements. In his account it had been Tryggvi and Saevar who had attacked Gudmundur, but Kristjan admitted he was very drunk so the events were a bit hazy. He described the drive into the lava fields and going past the plant at Straumsvik too. Kristjan appeared in court and confirmed the statement he had given to detectives that Gudmundur had been killed in Saevar and Erla’s apartment and they had brought him to the lava fields and dumped him in a pit and put a big stone over the spot.

The detectives needed the confessions as eyewitness testimony was in short supply, despite the fact that Hamarsbraut was a peaceful road, the kind of place where the neighbours would hear any disturbances. Regardless, the detectives now had detailed accounts of Gudmundur’s final hours from all of the suspects – even if they were not ‘clean’ confessions. The accounts were filled with imprecision and vagueness about certain key details. The motive seemed to be that Gudmundur had been killed in an argument over who should pay for alcohol, with each of the suspects blaming the others for Gudmundur’s death. But confessions they were, from the killers and their accomplices. In Iceland, where 90 per cent of convictions were secured with confessions, this was vital. Among the police and investigating magistrates, getting a confession was valued above all else.

Saevar had developed a reputation as a player, particularly in the mind of the customs chief, Kristjan Petursson, who had questioned Saevar on several occasions in the preceeding years for potential drugs offences and even for a major robbery. The Reykjavik detective Arnprudur Karlsdottir knew of Saevar as a small-time drug dealer and never understood Petursson’s obsession with him as a one-man crime wave, ‘It was very strange in my mind and we would talk a lot about it – why is Kristjan Petursson always after Saevar?’ The police could see that Petursson was frustrated by his customs role and wanted to expand his empire and get involved in investigations rather than just seizing goods at the airport.

Petursson had made his suspicions about Saevar clear to the detectives. Through their questioning over the post office embezzlement, the team saw Saevar as a devious liar who had tried to fool them. His role in the Gudmundur case now made him a serious criminal. If Saevar was capable of one killing, were there other unsolved crimes he might be responsible for, too?

6

January 1976

For six months, the manila folders containing the 70-odd typed statements and evidence on Geirfinnur Einarsson’s disappearance had been gathering dust in the office of Keflavik magistrate, Valtyr Sigurdsson. On 30 December 1975, a week after the arrests for Gudmundur’s murder, Valtyr had been asked to send over all the Geirfinnur files to the state prosecutor’s office.

A week later, Valtyr drove along the Reykjavikvegur through the lava fields to the capital. Here, according to the suspects, underneath the bracken and moss, was where Gudmundur lay – and perhaps Geirfinnur too. When Valtyr reached Reykjavik, he handed over all of the documents to the office of the chief prosecutor: the files about Geirfinnur’s finances; the statements from his wife, Gudni, from her lover, and from Geirfinnur’s boss; even the clay head. There were problems with the documents; many of the statements had not been signed, for instance, making them useless as pieces of evidence. Valtyr was glad to finally get the case off his plate.

On the same day as Valtyr’s visit, an article appeared on the front page of the left-wing newspaper Althydubladid with the headline: ‘Is Gudmundur’s disappearance linked to the Geirfinnur case?’ The report said four people were already in custody for Gudmundur’s disappearance, which now looked like a murder case.

It seemed like mischief making and speculation from the press, but the story didn’t come out of nowhere. The idea of a link between the two cases had been taking root in the detectives’ minds for a while. They now had the Geirfinnur case files and were trying to find any links between him and the suspects in custody. They just needed someone to help them flesh it out. And they knew exactly who to turn to.

Having been released from custody, Erla Bolladottir thought it was only a matter of time before the police realised her story was not true and the others in Sidumuli joined her. Although she was no longer in a cell staring at the flat, smeared walls, she was in a different kind of prison, racked with guilt. It was her statement about the body in the sheet that led to the arrest of Saevar and his friends. She still thought the detectives would see that her statement had been constructed with their help and prompting and that, as they investigated the case further, her tale would unravel. The reverse was true; the police wanted more from her.

Sigurbjorn Eggertsson had started calling Erla as soon as she was released. It seemed to her like a genuinely kind gesture, an effort to see if she was coping and needed any help. After a few days, though, he phoned with some startling news. ‘You can rest easy now,’ he reassured her, ‘because Saevar, Kristjan and Albert have confessed.’ He told her their stories matched Erla’s one hundred per cent, down to the last detail. For Erla this was seismic. ‘That was the point in time,’ she recalled, ‘where I lost all sense of what was real and what wasn’t, what was true and what wasn’t.’

Her already shaky hold on what happened that night in January 1974 started to waiver further. She had been sure the voices at the window had been a nightmare, that what she had told the police was a fiction. She recalled, ‘I didn’t have one memory of any of it and I still remembered clearly the real night that happened.’ But when three other people

had told the police the same story, she was filled with new doubts – ‘Maybe the police had a technique I didn’t understand and they had managed to get the whole truth out of me even without me being able to connect with it in my own mind.’ Perhaps the dream that had haunted her for so long was real, and maybe she had witnessed the aftermath of a murder in her apartment after all. How could she have locked this away for so long without it bubbling up to the surface?

With Saevar in prison and estranged from most of her family, she had moved in with her mother. During her relationship with Saevar, he had controlled her access to her friends and now she had few visitors. But there was one regular caller: Sigurbjorn Eggertsson, who would make unannounced visits. Erla lapped up this warmth and attention. For her it was ‘water in a desert, someone listening to me and caring for me’. Sigurbjorn was empathetic and a great listener. She responded to this warmth: ‘I would pour my heart our and he would be really nice.’

There was nothing left for Erla in Iceland. She wanted a new life, to get away from Saevar, her family, the hateful case and the lies she had spread. In January 1976 she decided to move to her beloved United States, to the warmer volcanic haven of Hawaii where her sister lived. She discussed this plan when she called on Saevar’s acquaintance, the former teacher Gudjon Skarphedinsson, in mid January.

Gudjon was surprised when Erla showed up at his home, but she clearly needed help. He felt she was ‘very nervous and very out of control’. As they chatted over tea, she told him about the threatening phone calls she had received at her mum’s house. The caller wouldn’t say much but had mentioned something that suggested he knew about Erla’s intention to go to Hawaii. They were trying to send a message that they knew her and her plans. The only people she had told were her mum and sister, who had told other relatives including her half-brother, Einar. This suggested the caller was someone close, someone who knew one of her relatives.

Gudjon could see she was terrified. He tried to reassure her, although he knew her plans to live in Hawaii were pure fantasy, as with the case active ‘there was no way she would be allowed to leave the country’. He didn’t dismiss everything she said, though, as he had received his own threatening phone call about the case. A man had rung asking if Gudjon knew where Geirfinnur was and asked to meet him at the bus station in Reykjavik to discuss it. Gudjon dismissed it as nonsense and hung up, but it was more significant than he realised. Whether he liked it or not, his name had started to figure in the rumours about Geirfinnur too.

If she stayed in Iceland, Erla needed someone to protect her, to fill the role that Saevar had assiduously guarded since she had become his girlfriend. With so few family and friends for Erla to rely upon, Sigurbjorn was only too willing to step in. Erla no longer saw him as a policeman investigating her partner, but as a friend. She told him about the threatening calls and he immediately arranged for armed police to protect her. Later Erla would wonder if the calls had been a ruse thought up by the police to draw her closer to them. But at the time, it confirmed her belief that Sigurbjorn was on her side, looking out for her, and that there were others who were intent on hurting her. She knew she didn’t want to let him down or offend him in any way.

The start of the new Geirfinnur investigation was not in a police station or in Borgutun 7 but in Erla’s old apartment. In January 1976 it was still sealed off by the police as a crime scene. Sigurbjorn had offered to help Erla get some clothes for herself and her baby from the apartment – just the kind of gesture that helped endear him to her. As she searched through the bedroom, Sigurbjorn asked her a question: ‘Is it possible that Saevar was involved in the disappearance of Geirfinnur Einarsson in November 1974?’ Erla was caught off guard. Where had this come from? She had been sure Saevar wasn’t involved in the Gudmundur case, but then he had confessed and her doubts had started. Now she was being asked about this totally new case. Sigurbjorn continued to chat, asking her what Saevar had said about Geirfinnur Einarsson. There was nothing that she could easily recall. As she sorted through the clothes she was still relaxed, telling herself this was just a chat between friends.

When Geirfinnur went missing in November 1974 it was big news, leading to much speculation and gossip. Erla recalled the clear ideas Saevar seemed to have had about the case, and the conversation she’d had with Saevar about the gossip linking the disappearance to the people who owned and ran Klubburin. Saevar had made barbed comments about Geirfinnur’s fate, ‘This guy was shooting his mouth off at the wrong moment in the wrong place, he only has himself to blame.’

This was enough of an opening for Sigurbjorn and standing inside her small bedroom, he probed further. What exactly did Saevar know about it? Erla was emphatic: ‘He didn’t know anything but he liked to look like he knew.’ She said Saevar always had ‘this Al Capone dream about getting away with the perfect crime that could not be solved’.

As they drove back through town, Sigurbjorn returned to the topic of Geirfinnur. When they pulled up outside her mum’s apartment he looked at her and said, ‘Do you know if Saevar knows something about what happened to Geirfinnur?’ Erla realised he was asking as a detective not a friend. This was turning into a police interview. Erla said, ‘My heart just dropped, all of a sudden this wasn’t just a chat.’ She hesitated, she was ‘afraid to upset him and his colleagues’, scared they would start treating her badly. She had come to rely on Sigurbjorn’s friendship and company. If she let him down maybe he would stop phoning her and visiting, which Erla didn’t want to happen. So she replied that she didn’t think Saevar knew anything. She pleaded with Sigurbjorn not to mention this to the head of the investigation, to treat it as just a private conversation between them. He promised it would stay that way, just between them.

The detectives’ version of this was very different. In a note in the police records they said that Erla had got in touch with them as she had been receiving threatening phone calls. When they spoke to her about this she said she was scared because of the Geirfinnur case. That was when they began their new inquiry into his disappearance.

The next morning after she had spoken to Sigurbjorn the doorbell rang at Erla’s mother’s house. She wasn’t expecting any visitors and she didn’t think Sigurbjorn would be back so soon. When she opened the door he was there, but this time he wasn’t alone. Next to him was the tall, leather jacketed figure of Orn Hoskuldsson. They invited themselves in, sat down on the sofa and Orn declared, ‘We have reason to believe that you have experienced something traumatic concerning Geirfinnur Einarsson’s disappearance and we are going to help you remember.’ Erla’s new nightmare had begun.

7

January 1976

The investigators were not going to settle for a cosy chat at Erla’s house. They needed to apply pressure, so they brought her back to Sidumuli prison, and the interrogation room where she had been broken before. Having got her to confess during the Gudmundur case, Hoskuldsson and Eggertsson knew exactly which buttons to press.

They started by asking what she did when Saevar was away on his ‘trips abroad’, when he disappeared, sometimes to buy drugs but on other occasions, both of them knew, into the arms of another woman. Erla explained how she spent a lot of time at her friend Hulda’s house. Hulda was the girl Saevar had been sleeping with when he first got together with Erla on their US trip. Hulda was quiet, a loner, who loved being with the more extroverted Erla, and Erla liked having a friend who was more grounded and not as angry as she was with the world. Being at Hulda’s house was fun; she had an older brother, Valdimar, who moved in a different world to Erla and her stoner friends. Valdimar’s friends were on the way up in Icelandic society: they were hotel managers, artists, businessman, and the people running Klubburin. To them, the world was full of possibilities that lay far beyond Iceland. They had the money to do as they pleased would throw parties where the drinks flowed. Erla remembered how one night they decided Iceland’s nightlife was too tepid and they would go to England instead. In no time at all they had char

tered a flight to England to party. In spite of her hatred of the capitalist system, Erla was impressed by their swagger. Orn and Sigurbjorn listened patiently as Erla talked and talked.

As the police had done with the Gudmundur case, Orn and Sigurbjorn spent hours talking about this time in 1974 when Erla had been extremely depressed. She didn’t want to reveal how lonely she was then, with so few friends. Lurking in the back of her mind was her eternal shame, the humiliation of soiling the sheet the night Gudmundur went missing. Erla said the police ‘sensed that, asking how I felt when I would get home from work and Saevar wasn’t there’. They were like the school bullies deciding to play nice but knowing where her weak points were and that they could hone in on them at any time.

Alone in the interrogation room with no lawyer present, Erla was once again being dominated by forceful men. She felt backed into a corner, giving away information, but she couldn’t stop herself. After hours of chipping away looking for an opening, Orn and Sigurbjorn knew Einar was their way in. The police knew Erla’s partnership with Saevar had strained her relationship with her big brother. Yet Erla still idolised him, she said in her eyes ‘he had a special place, he was like a god’.

The Reykjavik Confessions

The Reykjavik Confessions